Showing posts with label quasi-Luddism. Show all posts

Showing posts with label quasi-Luddism. Show all posts

20 July 2013

au Natural

Both the Stoics and the Epicureans advocated living according to nature, though each sought inspiration with different eyes. The Stoics believed in a universe bound up by a divine plan, and that a life of virtue meant living according to that plan, accepting what happened as the will of God -- or cosmic fate. Deities and their wills were more immaterial to the Epicureans, however, who saw more chaos than order in the cosmos and believed virtue lay in making the best of what we were given, of enjoying life while it lasted. There is wisdom in learning to adapt to whatever life throws at you, just as there is wisdom in enjoying it fully and not getting too distracted by mental chatter -- but there is more to living naturally than either.

What does it mean to live naturally? Outside of culture, beliefs, and ideology, human beings are fundamentally members of the animal kingdom in full standing. We use ideas to put distance between ourselves and that kingdom, but we are its subjects at every moment of the day whether we think we are or not. We are motivated by the same needs and instincts as every other animal on the planet, even if we dress those instincts up as feelings. Our instincts and needs are the products, not of perfect creation, but of imperfect evolution, of millions of years of trial, error, fix-it-on-the-fly biological compromise. To live naturally, first, is to respect that fact.

Before going forward, however, there is the matter of the naturalistic fallacy to address. Just because something is Natural does not mean it is good, or to be desired. Wariness and hostility toward strangers might be a natural instinct, but in modern times, chances are that the sudden arrival of group of strangers will not be a raiding party intent on killing your young, eating your fruit, and kidnapping your sisters -- a scenario our genes may be expecting when they produce anxiety in us at the appearance of an unknown person. Here is the wisdom of philosophy, in teaching us to overcome instincts that work to our detriment. However, we will presumably function best in the environment in which we evolved. That environment is not limited to the physical climate, but includes the kind of behaviors we're allowed to enact, the relations we engage in. Thus, humans are happier with one another than alone; we are happier sheltered from inclement weather than exposed to it; we are happier eating fresh food than rotting.

We must be conscious of our status as natural creatures, because instincts will manifest themselves with or without our permission. Hierarchies are ubiquitous among social animals, for instance, and in mammals there is often an alpha individual who rises to the top through strength, cunning, or in the case of certain primate species, cunning. Why then are we so surprised at the regularity with which political systems produce strongmen, and our easiness in accepting them? That monarchies persisted for so long, and that democracies become oppressive, is less a condemnation of political organization and more a mark against the systems which allow our natural weakness to lead to unnatural brutality. If Hitler had been the alpha male of a group of hunter-gatherers, the same strengths which brought him to power might have let him lead the tribe against threats -- and if they did not, or if those strengths failed him, he could have been displaced with ease. Civilization, however, has given alphas armies to expand their own power beyond natural limits, and given them means (like tradition or media outlets) to control by influence what they cannot touch by brute force.

We cannot turn back the clock and become hunter-gatherers. We must learn to work within the limits of our biology. In the realm of politics, the most rational response to our hierarchical weakness is to decentralize power as much as possible. Charismatic, strong, and cunning individuals will rise in every population and hold influence over people, but there is no reason their power must metastasize and become cancerous, dementing and corrupting them while abusing the public. Despite the lessons of the 20th century, political power, especially in the United States, is tending to become even more centralized, a trend that needs desperately to be reversed. Equally problematic is the power amassing in corporate entities, who are just as liable to tyranny as politicians, but who are even more wily, turning the very chains of regulation that we try to bind them by into weapons to whip their rivals and opponents with.

There is more to 'natural living' than politics, however. Evolution is starting to guide medicine more than in years past: we are now realizing that dropping anti-biotic bombs into our guts isn't the wisest course of action given our dependence on some bacterial species for basic processes like digestion. Some researchers suggest that our bodies need 'hostile' bacteria in them just to give our immune system something to do: otherwise, it attacks its own body. Or take matters of diet: just as a cat would not fare well on salad, or a dog on plankton, or a koala on anything other than eucalyptus leaves, so do we not fare well on many of the modern 'foodstuffs' filling the grocery store. In recent years a 'paleo' diet movement has arisen, maintaining that people should eat what we evolved to eat: meat, fruit, nuts, and some vegetables, leaving behind artificial food products like snack cakes, rolls, margarine, and imitation crab meat.

Many of the problems we face are caused by our attempting to live as something we are not, as creatures in a world of our choosing. We cannot drastically change our circumstances of living and expect the consequences to be marginal. We create an environment filled with fake food and no opportunities for the physical exertion our bodies were designed for, then wonder why obesity and diabetes have soared. We allow children to keep themselves overly stimulated with games on their tablets, or force them to sit in a box for seven hours a day quietly listening, and then label mark them as having attention deficit disorder. Perhaps it is our way of living, not ourselves, that are disordered. Maybe if children were taught the way they were evolved to be taught -- in the field, through the experience -- and played as they evolved to play, skin on skin with physical playmates -- they would not be bundles of neuroses. Perhaps if adults spent more time with one another and their families, and less time slaving at jobs producing profits for other persons, or stuck in traffic, they would not be as easy marks for depression and energetic religions.

Truth be told, I don't know what it means, entirely, to live naturally. I have some ideas, which is why I eat real food, voted libertarian in the last election, and practice simple living. In abstract, I can only say: to live naturally is to embrace our humanity -- to guard against our weaknesses while revelling in the experience of being human.

Labels:

flourishing life,

politics,

propriety,

quasi-Luddism,

simplicity

04 March 2012

Confessions of a quasi-Luddite

Recently I surprised a blogger at the KunstlerCast forums when I mentioned my minimalism regarding cellphones. I currently don't have one and rarely miss it: when I did own one, I kept it turned off until the late evening after my day of activity was over. My friends and I didn't need phones to keep up with one another, so I used mine to keep in touch with family. It doubled as an alarm clock. Unlike most of my generation, I never took to the cellphone. Early on I despised the way people answered them in the company of others, even at the dining table, and regarded the practice of talking while driving madness. I endeavor to keep the phone in its place -- turned off, and hidden deep in my pockets.

I suppose it is a little unusual that someone as young as I would have such a hostile attitude toward technology. I did grow up in a generation where being tech-savvy was the norm. Not a year went by without producing some new toy -- new game machines, watches with more features, CD players, mp3 players, etc. I used to keep up with it; I subscribed to appropriate magazines and spent long hours in the Electronics section of superstores, looking at all the wonderful stuff I might someday have. And yet, as I grew older, the allure faded. The constant stream of novelty began to bore me, as experienced prompted me to realize that no matter how excited people grew about one object or another, in a matter of months it would be broken and forgotten if not rendered obsolete by yet another gadget. By this time I'd entered the workforce and started to learn the value of money -- and for me, gadgets simply weren't worth my time and labor.

Beyond the factory, I've grown less starry-eyed about the advance of technology in general. I don't think our lives are actually improved by bigger televisions, smartphones, and monstrous vehicles with built-in TV players. History informs me that there are no actions without consequences, and the way people eagerly embrace changes without considering where they might lead concerns me. Take, for instance, cellular phones. I'm indebted to Neil Postman for giving me the vocabulary to articulate why the things bother me so: the ability to be connected constantly seems to have convinced people that we ought to be connected constantly, and moreover that there's something WRONG with not being connected. I for one like my privacy. I value solitude and quiet, and I truly despise the racket of a television and the obnoxious electronic whine of a phone. Every time one rings at home, I contemplate smacking it with a hammer. This ability of people to constantly demand one another's attention strikes me as entirely uncivilized: it is a medium of communication that demands virtually no consideration on our part, and the way people use them bears this out. They pull them them out everywhere, answer them everywhere, and let the world go by while their faces are drawn evermore frequently to a glowing blue screen, creating or reading some grotesque abortion of a sentence in English. Such is the practice of 'texting'.

Another example is that of automation. The term Luddite derives historically from a community of people who were angered that automation was rendering their work irrelevant. Their livelihood had been destroyed by machines, and rightfully they struck out against them. While I acknowledge that automation has made goods cheaper, I am also ever mindful of the human cost, and I cannot support its expansion unless some accommodation is made. I'm thinking of the other costs of automation, though: energy and the consequences of human inactivity. Although the US is in a prolonged energy crisis and over a third of Americans are obese (and susceptible to attendant health issues, like diabetes, hypertension, and cardiac woes), we insist on making life easier for people. We have constructed a society where most people MUST drive to get anywhere, by creating places unsafe to walk and bike, and spreading destinations across so wide an area that walking isn't remotely practical. Our homes are filled with 'energy-saving' appliances that force complete reliance on electricity, even when they're not in use. Considering that we are still relying on fossil fuels -- of which, in accordance with the laws of the universe there must be only a finite supply -- to power all this, the system is patently unsustainable. This is folly. We have made our lives so easy that we have to schedule time for 'exercise', whereas once we actually had to participate in life. I've come to believe that effort gives life meaning.

And so, for the last year or so, I've been phasing out dependence on some forms of technology when I can. I do this in part because I place so much value on sustainable -- reasonable -- living. I do this also because it makes my life simpler, quieter, and imminently more pleasurable. There are fewer distractions to badger me, and fewer drains on my resources. I'm evermore free to focus on the things which matter to me; the joy of living.

It's not that I'm a technophobe or an Amish convert. I'm enthusiastic about scientific advance and technological progress, but I don't confuse the latter with human progress. I simply believe we should be more mindful of our relationship with technology, considering its consequences. It's no more sensible to embrace novelty for its own sake than it is to cling to tradition for the sake of tradition. We should embrace or reject ideas based on their impact they have on our ability to enjoy happy, meaningful lives. A humanist in all things, I believe our actions and habits should be examined in the light of what they do for us -- or to us. We should be the masters of our tools, not the other way around, just as tradition and culture should serve us and not be our masters. So the next time the phone rings during your dinner, or while you are in the shower or reading a book, exercise your dominance over the phone. Don't answer it. Don't worry about it. And if keeps ringing, smack it with a hammer.

(Works for me.)

Related:

"TV and Me"

02 March 2010

TV and Me

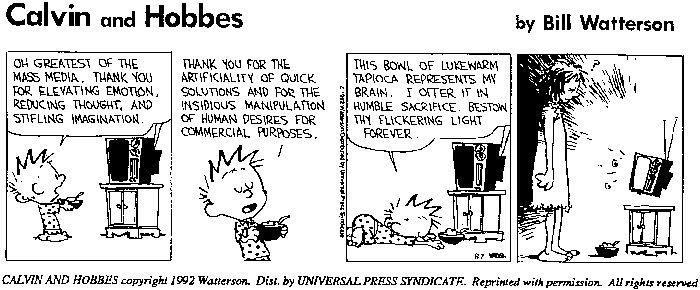

(One of the many Bill Watterson strips that I've appreciated more as an adult than as a child reading them in the newspapers.)

I have a curious relationship to television. I knew it rarely as a child: television sets were barred from my parents’ Pentecostal home, and so we only saw shows if we visited friends or relatives or stayed a motel. Like all children, I assumed what my parents said was true and right to follow, although the rule made increasingly less sense as the years went by. Why could we watch Full House at my aunt’s house, but not at our own?

Eventually television found its way into our home in a very limited form. It never became a central pillar of my life, although I did grow accustomed to a routine of shows and thought my life ill-served if I missed one. When I moved into college dorms for the first time, I gained access to cable television on a constant basis. If I wanted to, I could spend every hour of the day watching something: sitcoms, dramas, documentaries, music, English football matches -- whatever I wanted.

And yet… I didn’t. I was experiencing no lingering conviction from my Pentecostal upbringing: the anti-television rule made so little sense that I was thwarting it before puberty, covertly hooking up an antennae to a monitor we used for watching VHS tapes to watch shows when my parents were away. What I was experiencing was the honest enjoyment of life, and had been doing so for a little over a year when I first gained cable access. I found everything mundane to be wonderful -- the skies, the trees, the sound of dogs barking and people talking, even the feel of grass under my fingertips. This was the result of my leaving the Pentecostal cult and realizing I was a Humanist at heart, someone who wanted to be in love with the world but who had before then been forbidden to.

Now I was madly in love, and television’s enjoyment seemed shallow by comparison. I could and at times did spend hours at a time immersed in the blue glow, but once the day ended I felt nothing but remorse for having wasted the day in such a manner. I cannot say the same of the days I spent under trees, reading Thoreau and writing in my journal, or walking around town with friends and discussing philosophy. Those days I remember vividly: they had a magic about them. I sometimes suspect that everyday could have magic about it, if we truly lived it.

As my formal education increased, my disinterest in television grew. I think this disinterest began when I became a skeptic and started spotting all of the advertising gimmicks in commercials -- the dishonest little tricks advertisers were up to. More significantly, the past two and a half years have turned me into a social critic, at least in private. After reading Neil Postman's Technopoly and Amusing Ourselves to Death, I wondered if his advice wasn’t valid. It resonated with the Stoic idea of only concerning ourselves with matters we could control. It seemed to me that Postman was right: people have grown addicted to being entertained by drama outside themselves.

Soon, every facet of my intellectual life was grumbling about television -- it became a tool of consumerism, a values-defining tyrant as despicable as organized religion, and a medium through which the economic elite manipulate the news in their favor. It reduces human conversations to exchanges of shallow, obnoxious one-liners while glorifying violence and prostituting human beauty and love. It’s insulting, insipid, and ignorant. Worst of all -- it’s noisy! How can a person think through that barrage of moving pictures and sound?

The irony of this is that while my parents go to a church with an official ban against television, they and nearly everyone else in that church possess a well-used set. Their son who has emphatically rejected Pentecostalism and its many decrees, meanwhile, only watches television if it happens to be on while visiting at someone else's home.

That I again have something in common with Pentecostalism makes me uneasy, and I do not like the possibility that I'm becoming a self-righteous snob where television is concerned. I find precious little to recommend television, however: what intelligent and humane shows I do like, I can find on Youtube sans commercials. On those happily rare occasions when I want to slip into a mindless hour, I have DVDs a-plenty of How I Met Your Mother, Boy Meets World, and the like.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)