The Mausoleum at Halicarnassus.

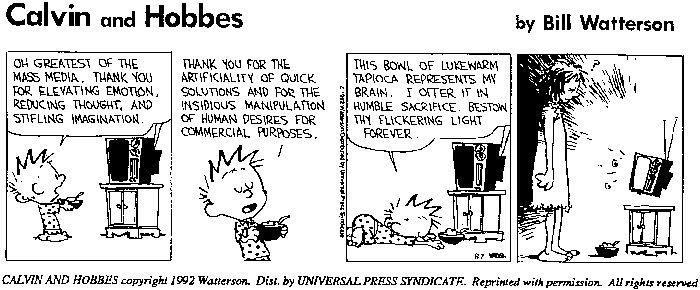

We live in a world ruled by rotting bones: cemetaries seat empires. The dead hold power that defies measure over the living. The dead reign largely because people are ignorant that corpses hold them in bondage. Few people would consciously bow before tombstones, and yet people carry on the bidding of decaying masters with every unconsidered thought, with every expression of an idea, belief, or value that they did not forge by hand themselves.

The dead rule the living because their ideas rule us. We become the property of despots as children, when we are most vulnerable, when reason's stern blade has not yet forged and tempered. Parents, society, and authority figures bind us, although they are slaves themselves. Sometimes they are conscious of the role they play as agents of tyranny, a role that allows religious sects and political ideologies to thrive. They perform the great trick of turning fetters into jeweled bracelets that we snap on happily and cling to. In enlightened times such as these, when people tacitly endorse freedom of speech and thought, they might feel somewhat guilty for imposing ideas on the innocent -- but then they feel it is righteous on their part. Every culture maintains itself: that's the way "it should be". Their political and religious ideas are

right, after all: what's the harm in making children think

right? In this way, all the horrible sects of the world maintain themselves, and children are taught to hate and are deprived of their potential. They are robbed the glory that lies in being free and living life with courage. Instead, the spear of Tradition beats their knees, forcing them to the ground where they bow before corpses.

Before Muhammed, people worshiped a box in Mecca that contained the relics associated with various Arabian gods. After Muhammad, they worshiped a box that contains a stone supposedly given to Abraham. Worship of the dead is still worship of the dead.

Our ideas are, in large part, not our own. We inherit them: to which decaying mounds of flesh we pay homage depends on where and when we were born. A family born in Rome four hundred years before the reign of Augustus would have kept an icon of a favored deity in their home, possibily of Apollo. Apollo's priests would rule there. Eight hundred years later, that same family would worship the doctrine of Paul. Paul's priests, his agents, would be that family's masters. Our parents give birth to us in the same gloomy prison cell in which they sit: they instill beliefs in us that their parents instilled in them. We call this cycle, this endless transmission of ideas, '

culture' -- and the promotion of one corpse over another '

progress'. Shall we allow an accident of birth to determine our beliefs and character?

I despise the rule of the dead, the tyranny of ideas over life. I reject their reign first on principle, for no human has any right to rule another in body, let alone in mind. Secondly, there is no reason we ought to be bound by tradition. Why should our ancestors rule us? What justifies the tyranny of parents, even? Maturity, intelligence, and a sense of responsibility are not required for procreation: the

lack of these traits seems

more conducive to arranging a pregnancy. Parents force themselves on their children, molding them into their own image, by the virtue of brute power -- nothing more. No one would contest their sacred right to produce copies of themselves, and so we are blessed with the heritage of racism and dogmatic religion generation after generation. It strikes me that the ability to mold a mind is a terrible responsibility, not a right -- one to be taken with humility and cautiousness, not pride. To the detriment of humanity, the only responsibility most parents seem to keep in mind is the' responsibility' to pass on the limited beliefs of their own parents.

Are the dead so much wiser than us? Hardly. They were human, just as we are, and prone to the same mistakes and indignities, and yet being dead seems to accord them great respect. The further removed they are from the world of the living, in fact, the more honor we give them. They can tell us they flew to Heaven on a horse and saw the dead walk again, and we

believe them. If the living told us these things, we'd gently escort them to the mental ward. I suspect we give the dead such honor because we feel we cannot take ourselves seriously, and so we cling to the ideas of people who are removed from us. We seek objectivity. But whatever noble personages we honor shared the same insecurity: Jesus looked to Moses, Plato to Socrates. They too, sought objectivity, for they were limited by their times just as most people are today. Moses thought nothing of murder, Jesus nothing of racism, Paul nothing of slavery. The United States' founding fathers beat their chests and spoke nobly of democracy while maintaining slaves and denying all but the landed gentry the vote. Few individuals are spiritual anarchists, who based their lives on their own hand-made ideas, beliefs, and principles. Those who do stand out, because they have found a more elevated foundation: ideas and morals based on free reason. If we are to seek objectivity, I believe reason is our best hope.

I understand part of the reason people cling to the fetters of their ancestors is the knowledge that one day they will become ancestors themselves. Every person who spends their first night in a crib will eventually spend their last night in a casket. In modern times we humans can live close to a hundred years: our ancestors would have thought fifty a boon. Even so, we know we are but leaves blown in the wind, simply passing through life. Cognizant that our time on Earth is short, we long to be linked to a tree.We seek meaning by attaching ourselves to something bigger: a religion, a state, a worldview. Perhaps this is unavoidable, but there is no cause for slavish attachment. If we wish to ground ourselves by referencing a tradition, why not do so with a level of sobriety, of knowing what we are doing and doing it with respect for ourselves. Even the mightiest oak will fall in time: I suggest it is better to make the most of the time we have than to hide ourselves in longer-lived traditions.

When it comes to "honoring" tradition, I think we take stock of ourselves and ask: are we maintaining tradition deliberately to serve us? Or...are we protecting it because we

depend on it, unaccustomed to living, thinking, and believing on our own? If we are trying to protect ideas to protect ourselves, we are not free. We cannot be free to live, to grow, to flourish if we're constantly hobbling on a crutch.

Too magnificent a jewel to waste on the hands of the dead.

For my own part, I believe Earth and life belong to us, the living. The dead have had their day. Let it rest with them. Ours is still upon us, and we ought to seize it -- to live

as

our needs and desires demand, not the putrefying flesh of yesteryear.

Foundations may crumble,

And structures will tumble,

And free men will cry,

"Die Gedanken sind Frei!"

But free men will cry,

"Die Gedanken sind Frei!"

("Die Gedanken Sind Frei", English lyrics by Pete Seeger)